By Heitor Augusto

*Originally published in Brasil de Fato, a progressive Brazilian paper.

For a Black artist, America represents a territory where his/her production strategies come face to face with the fear of being consumed by the game of capitalism. By extension, for a Black person America constitutes an experience that may range from physical ecstasy and poetic expression to the brutal interruption of life itself.

This is one possible interpretation of the music-video This is America, the latest bomb dropped by Childish Gambino. Brought to the world last weekend by Gambino – the alter ego of the writer, director and actor Donald Glover, Atlanta’s creator –, it conveys such power and multiplicity of signs that it invites an obsessive analysis of its images.

Those who are familiar with Childish/Donald’s works are aware how futile it is to try to definitively interpret their meaning. His writing, acting, singing, directing and performing fully embrace titillation and discomfort as mandatory components of a meaningful audiovisual experience. Once you step into his territory, you better be ready to be dazed and confused.

I would argue this is the third time that the multidimensional artist has executed something highly disruptive. Atlanta was his platform the two previous time. The first time I felt this perplexed was after episode seven, B.A.N., a refined satire of the content broadcast by B.E.T. A few minutes into the episode all of my certainties were imploded and I was left only with a feeling of confusion: in which side of the play is Donald Glover? And how about me: as a spectator, who am I supposed to side with?

The second disorienting event took place during episode six of season two, Teddy Perkins. A profound and unavoidable sensation of melancholy and pain ran through the whole experience. Once it was over, I couldn’t think anything but “WHAT THE FUCK JUST HAPPENED?!”

A crucial aspect of those two works as well as This is America is how they point to a Black artist who is committed to reflecting upon the black experience of “being turned into the Other” – echoing some analytical points from Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks – but, more interesting than that, he is curious to investigate and establish a dialogue from Black to Black, bringing to light a number of reflective and critical topics relevant to the Black community. Childish/Donald doesn’t side with non-critical, romanticized perspectives. He would rather toy with contradiction.

Echoes and signs in This is America

The clearest echo reverberating throughout the whole music-video – from his facial expressions to his arched back, from the choreography to the gaze staring right into the camera in almost every shot – is the black entertainer. He, the black subject who entertains and is under someone’s gaze when performing in a public arena, expressing himself creatively. He embodies the historicity of all the creative exchanges from the Black Atlantic [1].

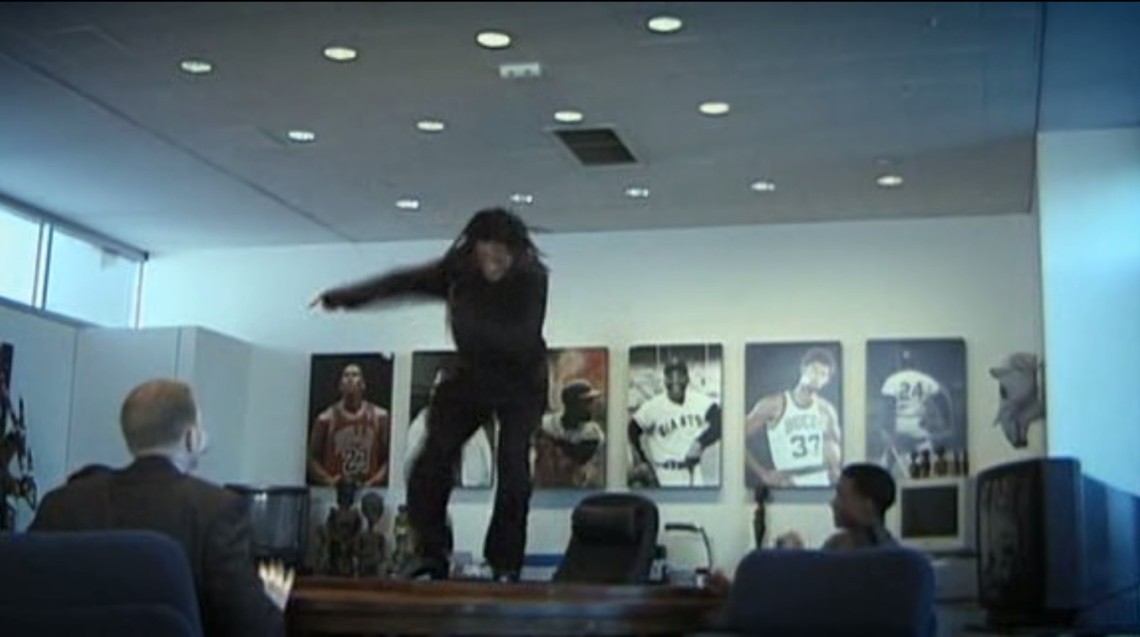

As Childish moves and smiles to the camera, we can easily recognize the 19th century minstrel shows, the symbology of the blackface, the systemic racism of the Jim Crow, the stereotype of the watermelon eater and Sambo. In this sense, This is America opens a straight line of dialogue with the criticism embedded in Bamboozled (2000), Spike Lee’s perhaps most underrated film, and takes an opposing stance to the racist celebration of the “happy Negroes” from The Birth of a Nation (1917).

Interested more in disrupting than organizing, Childish doesn’t shy away from pointing out white America’s responsibilities in having shaped, through a racist frame, the black as a sign and having contributed to the physical and symbolic deaths of Black People. However we can’t ignore that This is America creates multiple layers of criticism. One of them is about the Black creator who is aware that, once he steps into the stage, he can be converted into a sign: the black who entertains, deprived from any humanity or subjectivity. We as Black people express ourselves because of – and through – our will and desire to live and our creative power. But how can we protect ourselves from being turned, because of our art, into the black court jester?

In interpreting all of the This is America’s layers, we must look at certain key details: e.g. that every single gunshot comes from a gun held by Childish himself; that every killing leads to a shift of the musical beat; that only Black bodies occupy the diegeses; that the song constantly modulates from frivolous happiness to a controversial atmosphere. Gambino/Glover is clearly aware of how crucial it is for a Black artist to learn how to navigate the contradictions. “This is America/ Don’t catch you sleppin’ now”, that is how the lyrics go. “Grandma told me/ Get your money, Black man”.

To create within the confines of a seemingly indestructible American capitalism is to have yourself surrounded by contradictions. Just ask Beyoncé [3], Jay-Z [4] or Kendrick Lamar [5]. In just two years Childish/Donald jumped from a promising voice to the new Black Messiah.

Underneath the surface

A large portion of Gambino’s music-video takes place in the lowest level of the building, where the black experience generate images of joyful black bodies. The choreography reflects expressions of the black contemporary youth through shoot dance, Roy Purdy and Silentó’s Whimp/Nae nae. On the surface – which is to say, the real world – the terror remains the same. At the end of the music-video, Childish’s character runs full speed, as if he was following the advice from the gardener turned zombie in Get out! (2017). In a work that provides us enormous material for reflection, the choice is for a close-up shot of a terrorized Childish as a closure, followed by a fade to black.

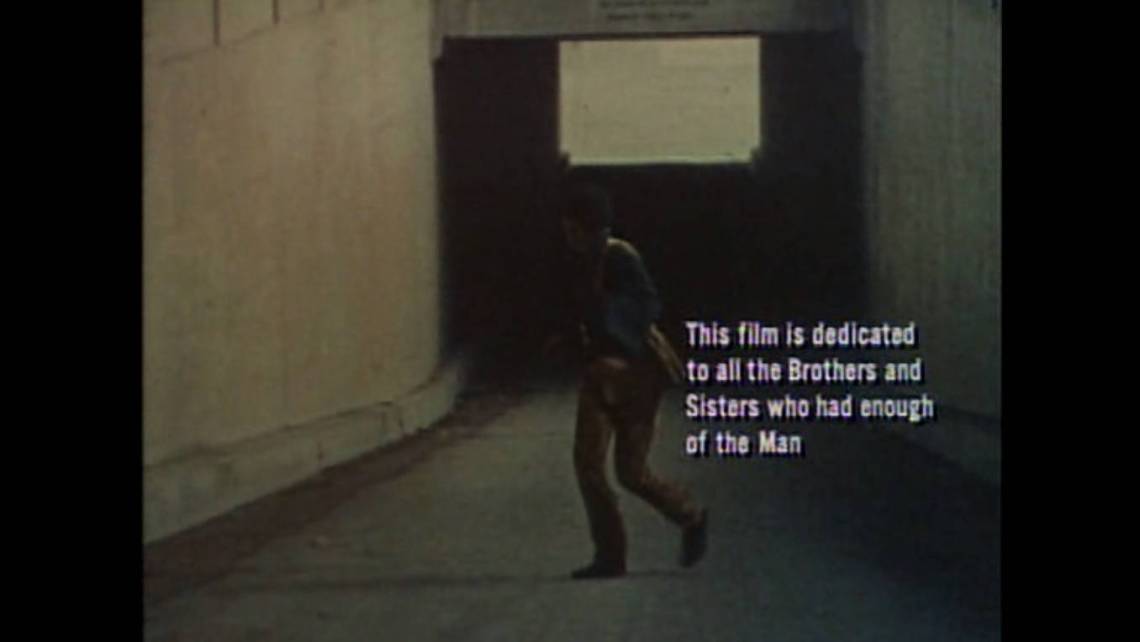

The United States national anthem brags that America is “the land of the free and the home of the brave”. Is it? This is America modulates the leitmotif of the black refugee within his/her own country, but on the move, as beautifully portrayed by Melvin Van Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss (1971).

“This film is dedicated to all the Brothers and Sisters who had enough of the Man”, says a title card of the movie. That also could easily be on Childish’s work, for it strongly communicates with those who experience, through the mere act of trying to stay alive, terror and contradiction.

One last word: who holds the camera in This is America? I ask this metaphorically, for we see Hiro Murai’s credit as director – Murai is a longtime collaborator of Childish/Donald – and Larkin Seiple’s as cinematographer. Childish and the rest of the cast perform straight to the camera, aware that they are being seen. With that being said, who has the agency of the gaze in This is America? Is it white America or Black America that holds the camera?

As in most of the artistic creations in which Childish/Donald is involved, there’s no indisputable answer.

[1] I recommend reading Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, in which the author investigates the Atlantic Ocean as a symbolic territory of active exchanges and remembrance.

[2] I’m not the first one to attest how, since Destiny’s Child, the idea of power from Beyonce’s music can’t be dissociated with the accumulation of capital and the subsequent power provided by having money.

[3] Since we are talking about the money-related power, I recommend a close look at The Story of OJ’s lyrics, 4:44’s second track.

[4] To Pimp a Butterfly is permeated with a deep concern of loosing one’s agency once you are catapulted to superstardom. This is a feeling explored by the first lines of the poem, fragments of which are inserted in several songs: “I remember you was conflicted, misusing your influence”.